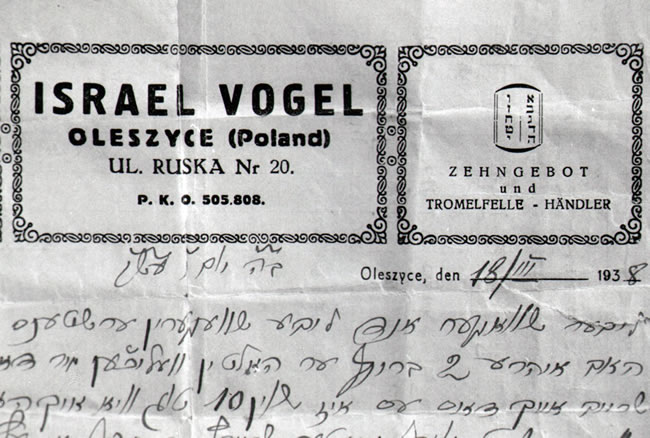

Israel Vogel’s Letter to Palestine on March 18, 1938

Israel Vogel was Eva Galler’s father. He was a much respected member of the Jewish community in Oleszyce, Poland. As the letterhead of his stationery indicated, he was a business man who sold Jewish religious “articles,” such as the Torah and prayer shawls, to Jewish communities in Poland and throughout Central and Eastern Europe. Oleszyce was renown for the manufacture of these articles. It was also renown for its large Hasidic population. The Rabbi of Belz lived in Eva’s house for several years after World War I. In this letter, written in Yiddish on March 18, 1938, to a relative in Palestine, Israel Vogel referred to the Nazi seizure of Austria that had taken place six days earlier, and to the money he will never collect.

Drawings by Eva Galler’s brother Pinkus Vogel

Our survivor Eva (Vogel) Galler grew up in Oleszyce, Poland. Her younger brother Pinkus was a gifted artist. As shown here, he decorated the margins of a letter written to relatives in Palestine. On January 8, 1943, Pinkus, along with Hanna and Eva, jumped from a “death train.”

Eva (Batszewa) Vogel and Henry (Henek) Galler were “sweethearts” (Henry’s term) in Oleszyce, Poland, before the war. They attended the same grammar school, although he was two years older. The war separated them. One year after the war, they were reunited by chance encounter. Some sixty years after the war, Bogdan Licz, a local historian, found Eva and Henry’s 1932 report cards. Henry was pleased to learn that he had received higher marks than his future wife. He was competitive to the last day of his life.

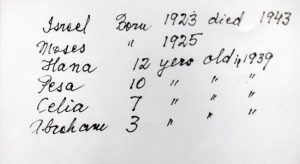

Eva Vogel and Henry Galler’s Siblings

Eva Vogel and Henry Galler grew up directly across the square from one another in Oleszyce, Poland. Seventy years after the war, Eva wrote a list of the names and ages of her siblings in 1939, and the same for Henry’s siblings. Not one person on that list survived the war. As noted, Eva’s sister Hana and her brother Pinkus jumped from a “death train” and were killed. Henry’s father and his brother Moses jumped from the train and returned to Oleszyce, hoping to find someone who would hide them. They were caught by the Ukrainian police serving the Germans and killed in the market square. Their bodies probably ended up in the mass grave at the Jewish cemetery.

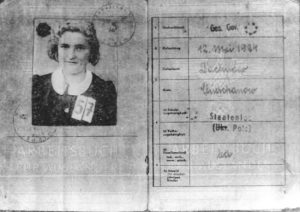

Eva (Vogel) Galler’s False Identity Papers

Eva Galler jumped from a “death train” on January 8, 1943. She walked back to her hometown and was given momentary shelter by two different women and then took a passenger train to Cracow. After spending three days in the train station, she was caught by German soldiers in a street round-up. They were grabbing Polish young people for labor in Germany. Pretending to be a Polish Catholic girl, Eva quickly invented a new identity. She chose the name of a former classmate, Katharina Czuchowska, and gave herself a different birthday and hometown. The Germans gave Eva new identity papers (Work book for foreigners) and sent her to work as forced labor on a farm in Austria. She survived the rest of the war “passing” as a Catholic girl.

Photograph of Einsatgruppe Killer

After the war our survivor Siggy Boraks married and lived for several years in Frankfurt, Germany. He befriended a young German named Kurt who gave Siggy a photograph of himself as a sign of friendship. But when Kurt learned that Siggy was Jewish, and Siggy learned that Kurt (a church going man) had been a member of the Einsatgruppen, the mobile killing squads that shot Jews in “the east,” the friendship ended. Kurt wanted Siggy to return the photograph but he refused. According to what is scribbled on the back of the photograph, it was taken at Charkov (Russia) in 1943. This city was retaken by SS and Wehrmacht troops in February-March 1943. Kurt wears a Wehrmacht uniform. His coat has fur lining around the neck. There is a story attached to this fur. In December 1941, after the Germans failed to take Moscow and winter caught them unprepared, Goebbels called for German citizens to donate their warm clothing (including furs) to the Wehrmacht for its freezing soldiers. This indicated to the German public how desperate the situation was in Russia, and how unprepared the army was.

Plaque at site of labor camp in Blizyn, Poland

Our survivor Siggy Boraks survived a year and sixteen months at the Nazi labor camp in Blizyn, Poland. There were both men and women prisoners in this camp. The majority were Jewish. The other prisoners were Polish. The plaque on the site of the former camp does not mention Jews, reflecting the intense anti-Semitism of the post-war period in Poland. There was little willingness to recognize Jewish suffering.

Partial membership list of the New Americans Social Club

When the survivors arrived in New Orleans after the war, they did not always feel welcomed by the local Jewish community. The survivors were mostly of Polish origin and the local Jews were mostly of German-Jewish origin. Historically there had been a deep gulf between the two. The survivors decided in the early 1960s (after confronting the American Nazi Norman Lincoln Rockwell) to form their own club, which they named The New Americans Social Club. On this partial list its members are the names of several of our survivors, including Felicia Fuksman (Max died in 1982), Eva and Henry Galler, Sigmund Boraks, Isaac and Dora Niederman, and Martin Wasserman.

The Meridian Star, February 1, 1939

Liselotte and Leo Levy, ages 17 and 14, immigrated from Nazi Germany to United States in January 1939. They arrived in New York City and caught a bus to Meridian, Mississippi, where relatives greeted them. They were interviewed by a reporter for The Meridian Star the next morning. The article about the two “German refugees” appeared on the front page that very afternoon. Nowhere was it mentioned that the refugees were Jewish. Such was the intense anti-Semitism of the time that the very word “Jew” was avoided.

Liselotte Levy’s German Passport

Liselotte Levy, born in Neuwied, Germany, received her German passport on Tuesday, December 6, 1938. Two days later she traveled with her brother Leo to the U. S. consulate in Stuttgart, Germany, and received her much coveted visa stamp. She and her brother departed for the United States aboard the USS Manhattan on January 17, 1939, nine months before the outbreak of war.

An examination of her passport offers insight into the workings of the German bureaucracy and its persecution of Jews.

Page 1

‘J’

Emblazoned on the first page of Liselotte’s passport, along with the swastika, is a large red ‘J,’ which identifies the bearer as Jewish. After Hitler seized Austria in March 1938, many Austrian Jews fled to Switzerland. The Swiss government tried to prevent this influx and insisted that the Germans identify the passports of all Jews with a ‘J.’ It is significant that the Swiss, and not the Germans, initiated this idea of marking the passports. There were not many places in the world were Jewish refugees were welcomed.

Sara and Israel

Liselotte’s name was Rosette Lieselotte Levy, yet she signs her name “Sara Rosette Lieselotte Levy.” (In America she changed the spelling of her name to Liselotte) In August 1938, to identify and further isolate Jewish people, the German bureaucracy issued a decree that Jewish women affix ‘Sara’ to their names, and Jewish men ‘Israel’ to theirs. ‘Sara’ and ‘Israel’ were seen as typically Jewish names and readily identified the bearer of the passport as Jewish.

Page 2

On page two of her passport Liselotte again signs her name “Sara Rosette Lieselotte Levy.” On this page is a stamp issued by the mayor’s office in Neuwied. The necessity of going to government offices, in order to receive various stamps for emigration, was a terrifying experience.

Page 3

On page 3 there is a biographical sketch of Liselotte:

Profession: maid

Place of birth: Neuwied

Birthday: July 7, 1921

Residence: Neuwied

Body type: middle, big

Face: oval

Eye color: gray, green

Hair color: black

No special features

Pages 4-5

On these two pages are stamps from various German offices that were required for emigration.

PAGE 6

Liselotte went to a bank in Neuwied to withdraw money and acquired another stamp on her passport. This was on January 14, 1939, a day before her departure for Hamburg where she would board the Manhattan for the United States. Scribbled on page six is “RM 9.90.” (RM=Reich Marks, German currency). This was the amount of money (the equivalent of a few dollars) that a refugee was allowed to take out of the country. Their property was seized by the German government, reminding us that the Nazis were thieves before they became murderers. But Liselotte was not permitted to leave the country with even ten Reich Marks, as ten Pfennigs were subtracted from that amount, presumably by the bank to pay for the transaction.

Page 7

The stamp on this page indicates that Liselotte departed from Hamburg (aboard the USS Manhattan) on January 17, 1939.

Page 9 Quota and Visa

When Liselotte went to the American consulate to pick up her visa stamp, she had to provide several documents and pass a mental and physical examination. The visa, confirmed by a stamp on an unnumbered page at the back of her passport, was signed by an American vice-consul, Julius O. Jenson. Liselotte’s quota number was 10218. This tells us that of 27,300 people (from Germany, newly annexed Austria, and newly annexed Sudetenland) in line to receive a U. S. visa that fiscal year, she was number 10,218. Liselotte and Leo were fortunate that their parents had the foresight to register them for immigration several years earlier. The U. S. quota was filled to capacity during only one fiscal year. When the war broke out in September 1939, immigration to the United States became very difficult and much more expensive.